This is a picture of me on the left with my friend Jack this past January at the National Western Stock Show (photo credit: Ken Claussen). I had by this time in January started following Covid-19, remembering my grandfather’s story of being discharged from medical school in Chicago to manage influenza-death bodies in 1918. Several of us at the National Western got respiratory illnesses shortly after this… was it Covid-19? Nobody in our group has tested positive to date, but the question certainly emerged during the following weeks. The National Western was the last organized event with crowds that I have attended to date.

Over the time since Covid-19 emerged, I have become increasingly involved in doing my own analyses, as I found the press coverage at first to be inadequate, and over time it has become distorted and frankly misleading. I am offended by the penchant of major media news to make entertainment out of news; “Panic Porn” as termed by Michael Moore. As a clinical faculty member at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and the Colorado School of Public Health I have had access to our state’s best developing data sets regarding Covid-19, and am happy to note that these data sets have been promptly and accurately reflected to the public by way of the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment (CDPHE). Here is the link I use: https://covid19.colorado.gov/

In setting the stage for my initial and subsequent analyses, I am committing to staying medical and avoiding political commentary as much as I can. However, I acknowledge that I have been active in medical politics for a long time. I had served as chairperson for the Colorado Medical Society (CMS) Workers’ Compensation and Personal Injury Advisory Committee for a number of years advocating for Colorado physicians regarding legislation and rule making that impact these two areas of medicine. More recently, I have been the inaugural chairperson for the CMS Prescription Drugs of Abuse Committee where I have advocated for Colorado physicians concerning drug abuse/diversion/addiction issues with the Colorado Legislature, the Division of Regulatory Agencies, the Governor’s office and with the Colorado Consortium for Drug Abuse Prevention. With these experiences in physician advocacy, I believe I have gotten a good feel for how medicine and politics interact in Colorado.

I believe that anyone, both medical and non-medical, who engages in serious debate about Covid-19 should carefully read this book:

Originally published in 2004, this edition has been updated through 2018 and includes information about the many recent influenza and coronavirus events that have preceded Covid-19. It is a labored and turgid read, as John Barry includes large amounts of information regarding the medical community of 1918 and about the political forces at work as the United States was mobilizing troops for transport to France because of World War I. But, it is uniquely informative and has a great deal of applicability to our current Covid-19 pandemic.

As I read the story of the 1918 influenza pandemic initially during this past March, a difference between the 1918 flu and Covid-19 immediately stood out. The 1918 flu had a predilection for strong young people, generally in their 20s, particularly the men that were being concentrated in military camps and on transport ships. Today CDC reports that the median age of people who die of Covid-19 is 71 years of age… of particular interest to me as I turn 67 this month!

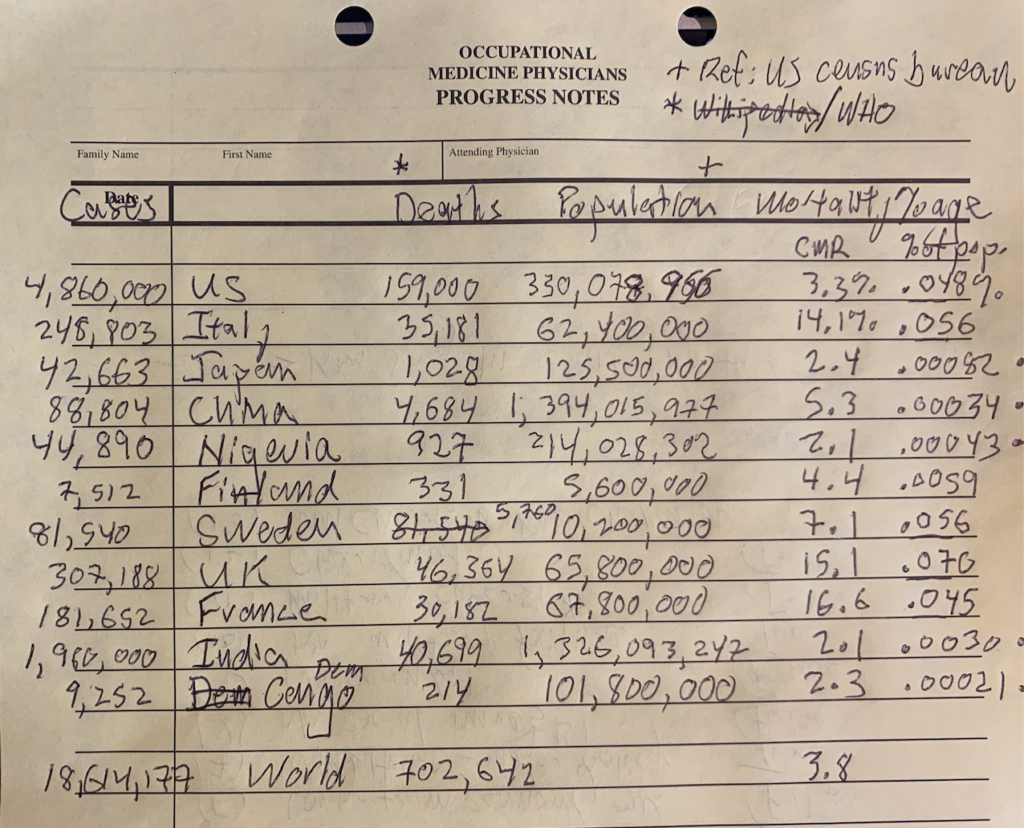

I have had people tell me ‘this is just the flu’ and grumble to me about all the shutdowns and restrictions… the new face mask mandates have really brought this out! So, here are the numbers – according to John Barry, on page 452 of his book, United States influenza mortality ranges from 3,000 to 56,000 per year, depending mainly on the virulence and also on the effectiveness of that year’s vaccine. To date, Covid-19 deaths in the U.S. so far in 2020 total about 159,000. So, this is not the flu, at least in a normal influenza season. However, in a 2009 influenza pandemic, one study revealed a regional case-mortality rate (CMR) of 13.5% – nearly as high as that Covid-19 in Italy where the current CMR is 14.1%.

Oh, I just spat out a statistic that I have not properly defined – sorry, my bad! CMR is the number of deaths divided by the number of cases in a defined population like Colorado or Finland. It is a central way to look at lethality, like with the current SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that is the Covid-19 pathogen. We really can’t use this statistic with the 1918 influenza, because ‘cases’ were not well defined then. But, it is useful now in the current pandemic and will become increasingly so as both ‘case’ and ‘Covid-19 death’ criteria are being refined.

Armed by information from John Barry’s book, let’s look at the conclusions drawn about the overall lethality of the 1918 influenza pandemic. He provided an “afterword” chapter where on page 450 he summarized and provided references for overall world mortality estimates. In his words: “…the pandemic probably killed 50 to 100 million people, with the lowest credible modern estimate at 35 million.” With a 1918 world population of 1.8 billion people, this works out to a lethality of 2% using the 35 million value, and a stunning 5% using the 100 million influenza fatality estimate. Even using the lowest estimate, 2% is a horrible level of lethality! Naturally, when I stumbled across this during March I was extremely concerned about where Covid-19 would go.

I have been interested in the relative experiences between Sweden and other Scandinavian countries. This cluster of countries is unique in that they largely share public health resources and have similar definitions for Covid-19 cases and deaths, so the comparisons are free of some of the other confounding factors I have encountered. Sweden largely did not shut down during the pandemic while the surrounding countries did. So, here is today’s data crunch:

Notice Sweden has a case-mortality rate (CMR) of 7.1% compared to 4.4% for Finland. Also, the proportion of deaths to total country population is 10x higher in Sweden compared to Finland. However, this is total aggregate data and does not factor in possible herd immunity that Swedes may have gained. Still, it is an interesting difference and may justify many of the restrictions we suffer under right now.

CMR is a slippery data point. Definition of ‘cases’ has been variable over the months and the sensitivities, specificities and predictive values of a positive test have been changing and not in a way that is easy to quantify. I am left making the assumption that a Japanese ‘case’ is the same as a Nigerian ‘case’… Somehow I doubt that is true!

Notice the U.S. has the highest number of both cases and deaths, yielding a CMR of 3.3%. Excluding the African countries and India (I will get there!) – notice that the U.S. CMR is lower than any other developed country that I collected data on other than Japan. Notice as well that the U.S. CMR of 3.3% is far lower than the U.K., France and Italy where CMRs were 15.1%, 16.6% and 14.1% respectively. That is a big difference!

So, CMR reflects the probability of death for an individual who contracts the virus and is found to be a ‘case’ included in these statistics. A high CMR may reflect the population has a large percentage of vulnerable individuals. I think Italy, the U.K. and France fit this category. Another possibility is that high CMR reflects poor health care quality. I don’t see how that would explain the differences between U.S./Japan/Finland versus Italy/U.K./France. I think the aged population demographic explains this particular difference.

These data also show evidence of highly variable Covid-19 penetration into the populations of the listed countries. While U.S., Chinese and Japanese CMRs do not vary much at 3.3%, 5.3% and 2.4%, the percentage of Covid-19 deaths per population tells a different story. In the U.S., there was a .048% death/population ratio compared to .00034% for China and .00082% for Japan! These data points lead me to conclude that both China and Japan have been more successful in preventing community spread of Covid-19 as compared to the United States.

How can I explain the low CMRs of Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and India? I really don’t have a clear answer; over the past month I have asked a lot of people about this and have gotten a lot of answers, like ‘the virus has not gotten there yet’, ‘they don’t have old people there’ and that their ‘case’ definitions, ‘death’ definitions and testing are deficient, particularly in Africa. John Barry writes and diligently referenced sources that cite true death and carnage in Africa and India as a result of the 1918 influenza. To date it seems this hasn’t happened with Covid-19.

Today’s conclusions:

- Covid-19 is not ‘just the flu’ – it is clearly important to prevent spread to vulnerable populations, particularly the elderly.

- Covid-19 penetration into a country’s population has been much higher in countries who stayed more open (Sweden) than shut down (Finland).

- Case Mortality Rates (CMRs) seem primarily to reflect age demographics (Italy) more than health care deficiencies (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

- There continue to be unanswered questions regarding the medical determinants of the Covid-19 CMRs.

- Currently the world mortality percentage for Covid-19 is .009% compared to the 1918 influenza mortality percentage range of 2-5% of the world’s population.